Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Considerations for Older Adults

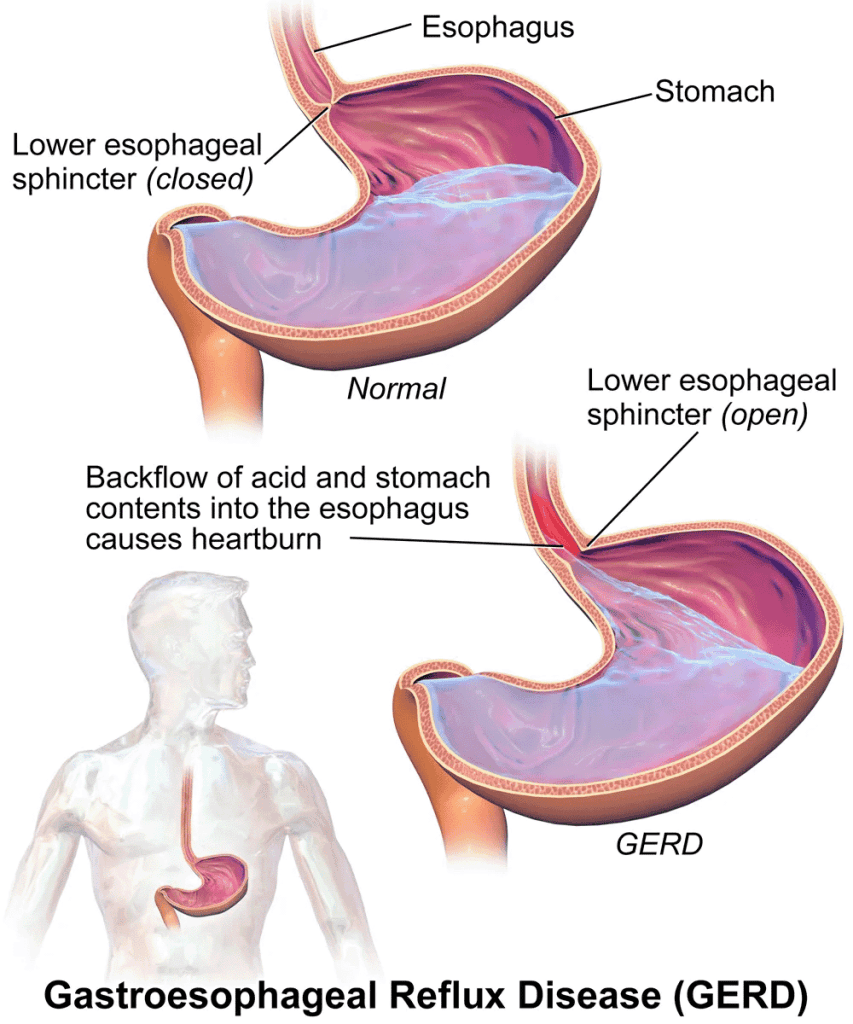

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) results from the reflux of gastric contents (regurgitation) into the esophagus due to dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and/or impaired esophageal clearance.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common upper gastrointestinal disorder seen in the elderly, and affects around 20% of the population in the U.S.

Factors such as increased intra-abdominal pressure and delayed gastric emptying contribute to relaxation of the LES, allowing acid and pepsin to enter the esophagus and damage the mucosa.

If GERD is not managed properly, it can lead to erosive esophagitis and/or Barrett’s esophagus.

- Erosive esophagitis occurs when the lining of the esophagus becomes inflamed and damaged due to repeated exposure to stomach acid and digestive enzymes. Erosion of the esophageal mucosa can lead to symptoms such as heartburn, chest pain, difficulty swallowing, and bleeding. Erosive esophagitis is typically diagnosed through endoscopy, where visible signs of inflammation, erosions, or ulcers in the esophageal mucosa are observed.

- Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the normal squamous epithelium of the lower esophagus is replaced by columnar epithelium with intestinal metaplasia. This change in the lining of the esophagus is believed to be a response to chronic exposure to gastric acid and bile reflux in those with GERD.

- Barrett’s esophagus is considered a precancerous condition because it increases the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. Diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus requires endoscopic evaluation and histological confirmation through biopsy.

Both erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus are complications that can develop as a result of untreated or poorly managed GERD. Therefore, early detection and effective management of GERD are essential to prevent the progression to these more serious conditions and reduce the risk of associated complications, including esophageal cancer.

Common risk factors for developing GERD include (but are not limited to):

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Alcohol consumption

- Pregnancy

Additionally, spicy, fatty, or acidic foods and drinks can exacerbate symptoms of GERD. It’s important to identify individualized GERD triggers and counsel or care plan avoidance for symptomatic patients.

- Caffeine (e.g., coffee, carbonated soda, energy drinks)

- Citrus fruits and juices (e.g., oranges, lemons, limes)

- Tomatoes and tomato-based foods (e.g., pasta sauce, salsa)

- Alcohol

- Fried food

- Spicy peppers

Clinical Presentation

GERD typically manifests as heartburn, described as a burning sensation below the breastbone rising towards the neck, and regurgitation, the return of stomach contents towards the mouth (often accompanied with an acidic and/or bitter taste).

Elderly patients have a higher tolerance for GERD symptoms compared with younger patients, and thus are less likely to report these symptoms.

They are also more likely to present with atypical GERD symptoms such as chest pain, dysphagia, respiratory symptoms (hoarseness, cough, wheezing), nausea, and vomiting, especially patients with erosive esophagitis. Unexplained weight loss, GI bleeding and anemia may also result from unchecked GERD in older adults.

Functional heartburn presents with symptoms similar to GERD, which makes differentiating between the two difficult based on symptoms alone. A key distinction is that functional heartburn will not respond to PPI therapy.

Initial GERD Management

Treatment of GERD in the elderly patient is essentially the same as in all adults with GERD. However, a more aggressive approach to treatment may be necessary in the elderly patient, because of the higher incidence and rate of complications.

Treatment goals for GERD include:

- Relieve symptoms and improve quality of life

- Promote and maintain healing of the esophagus

- Prevent complications of GERD (e.g., erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus)

The first step in the management of GERD is implementation of lifestyle modifications such as avoiding GERD triggers, elevation of the head of the bed, not eating within 3 hours of sleeping, and weight loss (when indicated).

Several medications can contribute to development of GERD or aggravate symptoms and should be evaluated by medical and pharmacy for safer methods of administration or alternatives in patients presenting chronic symptoms or with esophageal irritation.

- NSAIDs

- Bisphosphonates

- Potassium Tablets

- Beta Blockers (i.e. propranolol, atenolol)

- Theophylline

- Calcium-channel blockers (DHP – amlodipine, nifedipine)

- Anticholinergic medications (i.e. oxybutynin, benztropine)

Pharmacological Management

The backbone of pharmacologic therapy for GERD are medications that are directed at neutralization or reduction of gastric acid. Agents in this class include antacids, histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA), and proton pump inhibitors. Antacids (e.g. Tum’s-calcium carbonate) are effective when used as needed for symptom relief.

In general, PPIs are recommended over histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) for the treatment of GERD due to evidence demonstrating superior symptom relief and faster esophageal healing.

PPIs provide more potent and prolonged acid suppression than H2RAs. Tachyphylaxis may occur with chronic use of H2RAs, leading to decreased efficacy and increased stomach acidity. The 2023 AGS Beers Criteria recommend to avoid H2RA therapy in those with a history or high risk for delirium, due to their potential to induce or worsen delirium in older adults.

Available data suggest no clinically significant difference between PPIs in terms of esophageal healing and symptom relief (despite demonstrated differences in acid suppression).

PPIs are recommended to be taken 30 to 60 minutes prior to a meal (instead of at bedtime), prior to breakfast when ordered once daily, prior to breakfast and dinner ordered twice daily.

Note: The following is a summary of PPI dosing regimens based on FDA-approved labeling.

| DRUG | EROSIVE GERD TREATMENT | NONEROSIVE, SYMPTOMATIC GERD | EROSIVE GERD MAINTENANCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexlansoprazole | 60 mg once daily for up to 8 weeks | 30 mg once daily for 4 weeks | 30 mg once daily |

| Esomeprazole | 20-40 mg once daily for 4-8 weeks | 20 mg once daily for 4 weeks | 20 mg once daily |

| Lansoprazole | 30 mg once daily for up to 8 weeks | 15 mg once daily for up to 8 weeks | 15 mg once daily |

| Omeprazole | 20 mg once daily for 4-8 weeks | 20 mg once daily for up to 4 weeks | 20 mg once daily |

| Pantoprazole | 40 mg once daily for up to 8 weeks | 40 mg once daily for 4 to 8 weeks | 40 mg once daily |

| Rabeprazole | 20 mg once daily for 4-8 weeks | 20 mg once daily for up to 4 weeks | 20 mg once daily |

Use the lowest effective dose of the PPI to control GERD symptoms and maintain healing of the esophagus. It is important to continually reassess the indication and dosage regimen of PPIs in older adults, although well tolerated short-term, long-term ( >6 months) acid suppression with PPIs has been linked to the adverse effects including the following:

- Intestinal infections (e.g., C. difficile)

- Pneumonia

- Bone loss and fractures

- Acute and chronic kidney damage

- Vitamin and mineral deficiencies (e.g., vitamin B12, magnesium, calcium)

For these reasons the American Geriatric Society’s 2023 Beers Criteria recommends to avoid scheduled PPI use for >8 weeks unless for high-risk patients (e.g., oral corticosteroids or chronic NSAID use), erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagitis, pathologic hypersecretory condition, or demonstrated need for maintenance treatment (e.g., due to failure of drug discontinuation trial or H2-receptor antagonists).

Older individuals admitted to the community care setting commonly carry a diagnosis of GERD and are prescribed proton pump inhibitors. Reviewing the prior medical record and discussing history with the patient or their family may reveal opportunities where deprescribing is appropriate. Chronic PPI use should be reserved for the high-risk conditions noted above, while monitoring for complications of long-term use.

Takeaways for Managing GERD in the Older Adult

- Recognize atypical GERD symptoms including dysphagia, chest pain and respiratory symptoms (cough, wheezing) are common in older adults.

- Address modifiable risk factors, identify and avoid the individuals’ symptomatic triggers, and evaluate current medication list.

- PPIs should be used at the lowest effective dose and duration

- Monitor long-term PPI regimens for potential adverse effects and periodically assess PPI regimens for continued need and indication.

References:

- Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56

- Fass R, Zerbib F, Gyawali CP. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Functional Heartburn: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2286-2293.

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587.

- 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023; 1- 30. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372